When was the first time you heard the term, “earthshine”?

For me it was while I was reading Arthur C. Clarke’s Earthlight, and there was this passage where colonists on the Moon looked up at Earth hanging in their sky.

Interestingly, for them, Earth wasn’t a distant marble, (as we usually picture it to be) but as this overwhelming presence, 40 to 60 times brighter than the full Moon appears to us. Clarke described how Earth illuminated the lunar landscape in blue-white light, casting shadows, making it possible to read by earthglow alone.

The idea that Earth, from the Moon, isn’t just another celestial object but a lamp, is just brilliant, and overwhelming. It’s like seeing your hometown from across the valley, of course it’ll look slightly different but good in its own way.

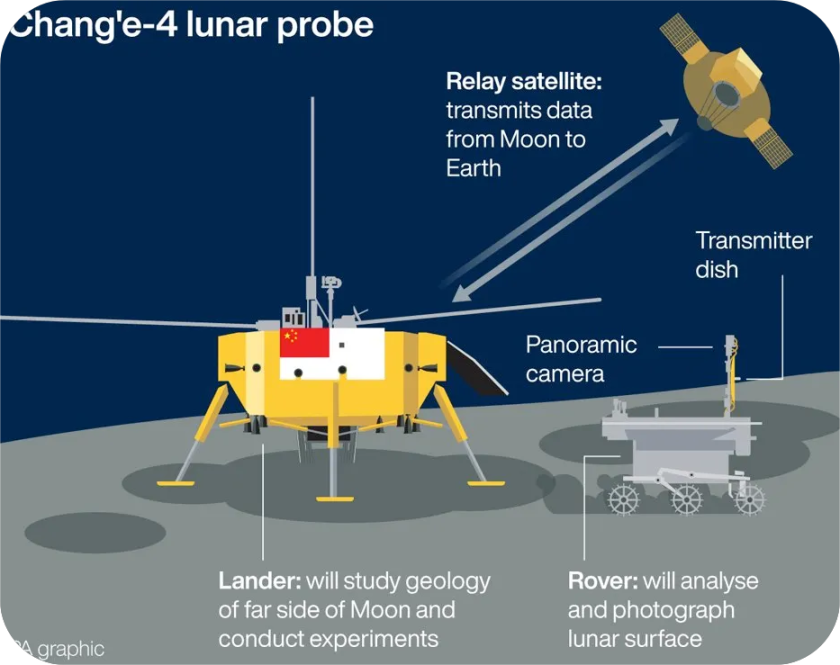

Last week, that childhood fascination came all over me when I came across a scientific paper about Chinese scientists using a device called LRO-III on the Chang’e-4 lander, which is sitting on the far side of the Moon in a crater called Von Kármán. They’re using this equipment to observe Earth’s radiation signals in a way humanity hasn’t done before.

They’re not just taking pretty pictures, they’re measuring Earth’s outgoing longwave radiation with unprecedented precision, essentially capturing our planet’s thermal fingerprint from 380,000 kilometers away.

The View From Von Kármán Crater

Chang’e-4 has been sitting on the lunar far side since January 2019, making it humanity’s first successful soft landing on that hemisphere. While most coverage focused on the rover exploring the surface or the relay satellite enabling communications, this lunar radiometer has been quietly staring at Earth for hours at a time, watching how much heat our planet radiates into space.

The research team from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, led by scientists from institutes in Beijing and Hefei, published their findings in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres.

I could find a similar streak in Robert Heinlein’s The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, where the Moon is imagined not as a frontier to be explored, but as a fully instrumented, operational outpost, an engineered system tied closely to Earth.

But the current research is no longer fiction because the measurements are real, the instruments are active, and data is streaming back from a working lunar station on the Moon’s far side today.

The instrument itself, a visible and near-infrared imaging spectrometer repurposed for Earth observation, captures Earth’s thermal radiation in the 10-12.5 micrometer range.

That’s deep in the infrared, the wavelength where Earth glows not with reflected sunlight but with its own heat signature.

Every object with temperature radiates at these wavelengths, it’s how thermal cameras work, how heat-seeking missiles find their targets, and how climate scientists understand our planet’s energy budget.

Earth Looks Different to Every Satellite Watching It

Here’s how climate science is connected to satellites gliding in and around our orbit.

Earth-orbiting satellites that measure outgoing longwave radiation, instruments like NASA’s CERES (Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System), do remarkable work. They’ve been fundamental to our understanding of climate change, energy balance, along with how much heat Earth retains versus radiates away. But they have a problem, they’re too close.

Satellites in low Earth orbit move very fast around the planet, completing an orbit roughly every 90 minutes. Because of this quick movement, they only see a small part of the Earth’s surface at one time. To get a complete view of the entire planet, they fly over the same areas multiple times, from different angles and under different weather conditions. By combining all these different images and data, they can create a full, comprehensive picture of the Earth’s surface.

It’s like trying to understand a symphony by listening to individual instruments at different moments, you can reconstruct it, but you’re always working with fragments.

Geostationary satellites orbit high above the Earth, about 36,000 kilometers away, so they can see large parts of one half of the planet at once. However, they don’t look straight down, they view Earth at an angle. This means their view through the atmosphere is different depending on whether they look directly downward or toward the edge of the Earth’s disk, which can cause distortions in their measurements.

The Moon is far enough away from Earth that it gives a clear, steady view of the entire planet all at once. From the Moon, Earth looks like a perfect round disk, small enough to see everything at once and far enough that atmospheric effects don’t blur the view.

It’s like standing back from a picture gallery and stepping back enough to see the whole painting clearly, rather than peering up close.

The Chinese team’s measurements show remarkable agreement with satellite data (correlation coefficients above 0.96), but with something extra:

they can see Earth’s radiation integrated across the entire visible hemisphere simultaneously.

No stitching required. No temporal gaps. Just Earth, whole and glowing, radiating its thermal signature into the black.

The Moon Is Becoming a New Kind of Climate Observatory

In many science fiction stories about space, a common idea is that when humans set up a presence on another planet or moon, it really shifts how we think about what “home” means.

In The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, Heinlein’s lunar colonists develop a completely different perspective on Earth and its politics because they’re literally looking at it from outside. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, both the novel and film, astronauts on the Moon look back at Earth with a philosophical clarity impossible from the surface.

What the Chang’e-4 observations represent is a softer version of that shift, not political or philosophical, but scientific. We’re using the Moon as an observation platform to understand Earth’s climate system in ways impossible from Earth itself.

Earth gets energy from the Sun in the form of sunlight and ultraviolet light. It then gives off heat energy back into space as infrared radiation, which is a longer wavelength of heat. The amount of energy coming in and going out needs to stay balanced, if more energy comes in than goes out, the planet warms up. If more energy goes out than comes in, it cools down. Small changes in this balance can lead to changes in the climate.

Greenhouse gases complicate this beautifully. Carbon dioxide, methane, water vapor, they’re transparent to incoming visible light but absorb outgoing infrared, temporarily trapping heat before re-radiating it in all directions, including back toward Earth. It’s not a “blanket” (that’s always been a terrible metaphor), it’s more like a delay mechanism in the planet’s thermal exhaust system.

What the lunar observations capture is the final result, how much radiation actually makes it through the entire atmospheric column and escapes to space. Different wavelengths reveal different stories:

clear sky versus cloudy conditions, day versus night, seasonal changes, even the heat signatures of specific weather systems.

Arthur C. Clarke Imagined This Kind of View

Reading through the research paper, I kept thinking about how Clarke got it so right.

In Earthlight, he described the Moon as a place where Earth dominated the sky, where colonists scheduled their work around Earthrise and Earthset in regions that experienced them. The novel focused on conflict and politics, but there were these quiet moments where characters just… looked at Earth. Contemplated it. Saw weather patterns forming, auroras flickering, lightning storms illuminating cloud tops.

Chang’e-4 is doing something similar, mechanically. It’s watching Earth with patient attention, measuring the subtle variations in thermal glow that indicate cloud formation, surface temperature changes, atmospheric composition shifts.

The instrument observed multiple complete Earth views between October and November 2019, capturing several diurnal cycles, full Earth-days as seen from the Moon.

One detail from the research is quite intriguing, which is, the challenges of calibration. The team had to account for the instrument’s own thermal noise (it’s sitting on the lunar surface, experiencing temperature swings from scorching day to freezing night), scattered radiation from the Sun and Moon, and the peculiarities of measuring something as large and variable as Earth’s thermal emission.

They validated their measurements against geostationary satellite data, showing the lunar observations captured the same large-scale patterns, but with better geometric consistency because the Moon’s orbital position relative to Earth changes slowly compared to satellite orbits.

Scaling Up the Moon as a Climate Observatory

If one lunar radiometer can provide this quality of data, what could a network accomplish? Just imagine instruments at multiple lunar locations, like near side, far side, polar regions, each watching Earth from slightly different angles, collectively providing continuous hemispheric coverage as the Moon orbits.

The research team notes that future Chinese lunar missions (Chang’e-6, Chang’e-7, Chang’e-8) will carry similar or improved instruments. There’s discussion in international space circles about establishing a lunar research station, China and Russia have announced the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) program, while NASA’s Artemis aims to establish a sustained lunar presence.

Climate science would benefit enormously from permanent lunar observation platforms. Unlike satellites with limited lifespans and fuel, lunar instruments could operate for decades with minimal maintenance (radiation-hardened electronics and occasional dust removal). They’d provide a stable baseline for long-term climate monitoring, crucial for detecting subtle trends in Earth’s energy balance.

A Brief Confession About My Excitement

I should probably explain why a non-scientist running a website about tech and science gets so excited about lunar radiometry that I’m writing 2,500+ words about it.

Some of it is just about feeling nostalgic for old science fiction, like seeing real projects that remind me of the stories I read by authors like Clarke, Heinlein, and Asimov who described things like lunar observatories, and now those ideas are actually becoming reality.

And then there’s a philosophical angel to it. For all of human history until the space age, we understood Earth only from within, from the surface, from ships at sea, eventually from aircraft and balloons. Even early satellites didn’t fundamentally shift that perspective, they just gave us a higher vantage point.

But measuring Earth from the Moon feels different. It’s observation from genuine distance, from outside the Earth-atmosphere system. It’s the perspective shift Clarke wrote about, where you stop seeing Earth as the world and start seeing it as a world, a planet among planets, a thermal radiator balanced between the Sun’s energy input and its own thermal output.

Measuring Earth’s Heat Isn’t Just Academic

I’ve been somewhat hesitant to make this article too climate-focused, because climate change discourse is exhausting and polarized and I wanted to focus on the cool science and the sci-fi connections. But I can’t write about measuring Earth’s thermal radiation without acknowledging why this matters so urgently.

Earth’s energy imbalance, the difference between incoming solar radiation and outgoing thermal radiation, currently sits around 0.5-1.0 watts per square meter globally averaged. That sounds tiny but it’s not. That excess energy, accumulating over decades, is warming the oceans, melting ice, intensifying weather patterns, and shifting climate zones.

Measuring that imbalance precisely is hard as you need to know:

- Incoming solar radiation (which varies with solar cycles and Earth’s orbit)

- Earth’s albedo (how much sunlight is reflected back to space, which changes with ice cover, clouds, and surface properties)

- Outgoing longwave radiation.

Each component needs measurement to within fractions of a percent for the energy budget calculation to be meaningful.

The lunar observations contribute specifically to that last piece, the outgoing radiation. And they do it with a consistency and geometric stability that satellite measurements struggle to achieve.

Climate skeptics sometimes argue that our measurements are too uncertain to trust. I find that argument frustrating because the physics of greenhouse warming is straightforward, but they’re not entirely wrong that measurement uncertainty matters. The more precisely we can observe Earth’s radiation balance, the more confidently we can detect trends, attribute changes to specific causes, and project future climate evolution.

A lunar observation network wouldn’t solve climate change, obviously. But it would provide a gold-standard dataset for validating climate models and detecting even subtle shifts in Earth’s thermal behavior over time.

The Observatory We’re Building

Each mission expands our presence and capabilities.

- Chang’e-6 successfully returned samples from the far side in 2024.

- Chang’e-7, planned for 2026, will explore the lunar south pole.

- Chang’e-8, targeting the late 2020s, aims to test technologies for lunar resource utilization, using lunar materials to build infrastructure.

- NASA’s Artemis program plans to land astronauts on the Moon by the late 2020s, with goals of establishing a sustained presence.

- The ESA, JAXA, and other space agencies have lunar ambitions.

- India’s Chandrayaan program continues expanding.

- Commercial lunar landers are becoming routine.

All of this infrastructure creates opportunities for Earth observation. A proper lunar Earth observatory, purpose-built, not just an instrument added to a lander, could revolutionize climate science, weather forecasting, and our understanding of Earth system dynamics.

In the future, some scientists might have grown up living on the Moon. To them, seeing Earth in the sky will be normal, just like how we see the Sun or stars. They will study Earth as if it’s just another planet to learn about, not a place they grew up on or call home.

That’s the perspective shift Clarke wrote about, the one that changes everything.

If you’re interested in the technical details, the full research paper is available in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres (Hu et al., 2026). The LRO-III instrument specifications and calibration procedures are described in supplementary materials.

Publication details:

Hanlin Ye et al, Spherical Harmonic Fingerprints Characterize Moon‐Based Disk‐Integrated Earth’s Emitted Radiation Signatures, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres (2025). DOI: 10.1029/2025jd044758

Frequently Asked Questions About Measuring Earth From the Moon

If you’re encountering lunar climate observation for the first time, these are the questions that naturally come up, and the ones I found myself asking while reading the research.

What is lunar radiometry?

Lunar radiometry is the measurement of Earth’s outgoing thermal (infrared) radiation using instruments placed on the Moon. Observing from the Moon allows scientists to measure Earth’s heat emission from a stable, distant vantage point, improving accuracy in climate and energy-balance studies.

Why measure Earth’s thermal radiation from the Moon?

Measuring Earth from the Moon provides a full, simultaneous view of the Earth-facing hemisphere. This reduces viewing-angle distortion and timing gaps that affect satellite measurements, resulting in more consistent observations of Earth’s outgoing longwave radiation.

How is lunar climate observation different from satellite monitoring?

Satellites orbit Earth quickly and observe small areas at a time, requiring data stitching across multiple passes. Lunar instruments observe Earth as a single disk, offering stable geometry and continuous hemispheric measurements that are harder to achieve from low Earth orbit.

What is Earth’s energy imbalance?

Earth’s energy imbalance is the difference between incoming solar energy and outgoing thermal radiation. When more energy enters the climate system than leaves, excess heat accumulates, leading to ocean warming, ice loss, and long-term climate change.

Why is outgoing longwave radiation hard to measure accurately?

Outgoing longwave radiation varies with clouds, surface temperatures, atmospheric composition, and time of day. Detecting small long-term trends requires extremely stable instruments and consistent viewing angles, which are difficult to maintain with orbiting satellites alone.

How does the Chang’e-4 mission help climate science?

Chang’e-4 demonstrated that lunar-based instruments can measure Earth’s thermal radiation with strong agreement to satellite data while providing improved geometric stability. This validates the Moon as a potential platform for long-term climate monitoring.

Could lunar observatories improve climate predictions?

Yes. Lunar observatories could provide a long-term, stable reference for Earth’s outgoing radiation. This would help validate climate models, reduce measurement uncertainty, and improve detection of subtle changes in Earth’s energy balance over time.